Chay Robert Rossing

1A. Introduction

“From its inception, the teaching of philosophy has thrived on the cornerstone of rigorous inquiry, demanding the dissection of ideas and the construction of robust arguments. Traditionally, the philosophy classroom has served as a crucible where these skills are honed, with students doing things like crafting essays and engaging in spirited debate. However, the recent advent of generative AI, capable of crafting human-quality generated content, casts a long shadow on this established approach. This paper contends that if the emergence of AI fundamentally alters how we value and assess student work, and the limitations of the current pedagogy become increasingly evident, then a critical reevaluation of our methods for teaching philosophy becomes not just a prudent consideration, but a categorical imperative. We must embark on a philosophical examination of our own pedagogical practices, ensuring that this pursuit of wisdom remains a space dedicated to genuine intellectual engagement and the cultivation of critical thinking, not one susceptible to mere mimicry by machines.”

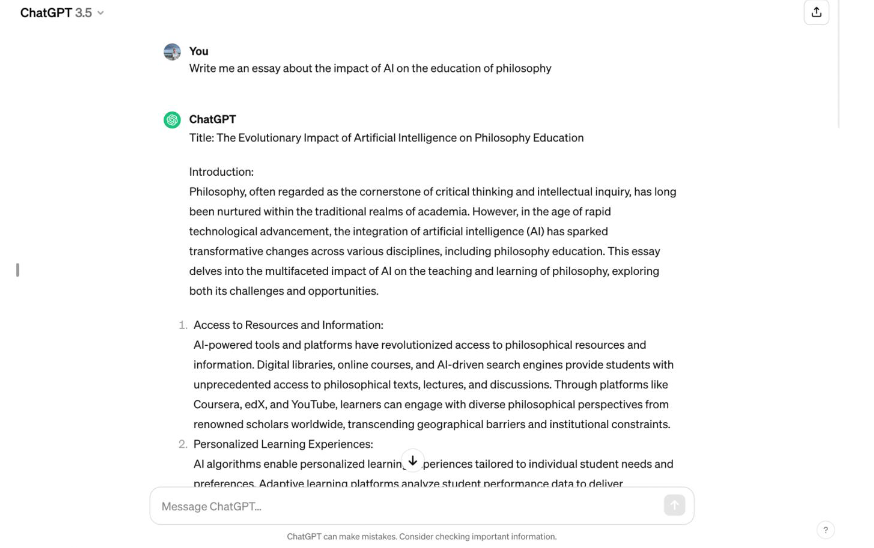

Everything you just read in that first paragraph was generated by ChatGPT.1

As ChatGPT has already so graciously explained, philosophy classes have historically earned themselves a reputation of being somewhat dense, esoteric, yet often rewarding courses for students – dominated by writing, reading, and discussion.2 Typically, goals and objectives regarding which skills a philosophy department is most concerned with their students developing are roughly analogous to those outlined in our own department here at Ohio State. Principally, that students should develop their ability to ask insightful questions, engage with the work of notable thinkers, improve their “clarity” or capacity to discern and condense their thoughts, and finally, that students refine their faculty to articulate these thoughts in both speech and in writing.3

However, recent developments in “artificial intelligence,” specifically that of easily accessible generative language models and chat-bots, naturally ushers in a corrosion, and now necessary re-evaluation, of our prevailing attitudes about what human composition, creativity, and originality entail. Most thoroughly developed in its up-ending the domains of natural language processing and computer vision,4 these generative AI models (such as the infamous ChatGPT) have demonstrated a remarkable faculty for crafting text, images, and even auditory content that verge ever closer to becoming indistinguishable from traditionally understood, human-generated content.

Thinkers, but especially educators, in philosophy, if we are to examine what exactly we value and wish to impart upon our students in the teaching of philosophy – no matter what exactly one might consider most valuable in their respective pedagogy – we find ourselves now needing to consider the core of ‘why’ we teach philosophy and what our goals are as educators in the first place. This new advance of AI-generated content brings into question our current methods of philosophical pedagogy.5 It presses us to consider whether our current methods for teaching philosophy remain pragmatically salient to our values and those reasons we give which underly our designated pedagogies, and furthermore, it brings into question what teaching philosophy might look like, going forward in this new landscape.

1B. Argument

Given this, I argue:

P1: If generative AI has created new complications in the way we value and assess assignments, and there are examples of current approaches to philosophical pedagogy failing us in assessing or prescribing value to these aforementioned assignments, then we ought to reconsider our traditional method of teaching philosophy.

P2: Generative AI has created new complications in the way we value and assess assignments.

P3: There are examples of current approaches to the pedagogy of philosophy failing us in assessing or prescribing value to these aforementioned assignments.

C: We ought to reconsider our traditional method of teaching philosophy.

Now, this argument was formed in such a way that it doesn’t assume, chiefly, much of what any specific pedagogy values – which was done so to avoid alienating varying perspectives and potentially instigating a response to my argument which posits an irrelevant conclusion. My purpose in defining this argument has been to spark some conversation within various ideological circles addressing the role of the current pedagogy in philosophy and the potential threat of instability moving forward. Claims about what we should value, and even whether or not traditional philosophy has totally failed, are claims which lie beyond my thesis here.

My argument, nonetheless, is an ethics-laden one. Considering this, I will assert the following moral presumption: that in the context of teaching college-level philosophy, at the very least, it is valuable for students to engage directly with a given class’s materials. I believe that this point is generally agreeable in that it benefits us, as a matter of practicality, to assume this to be the case moving forward.

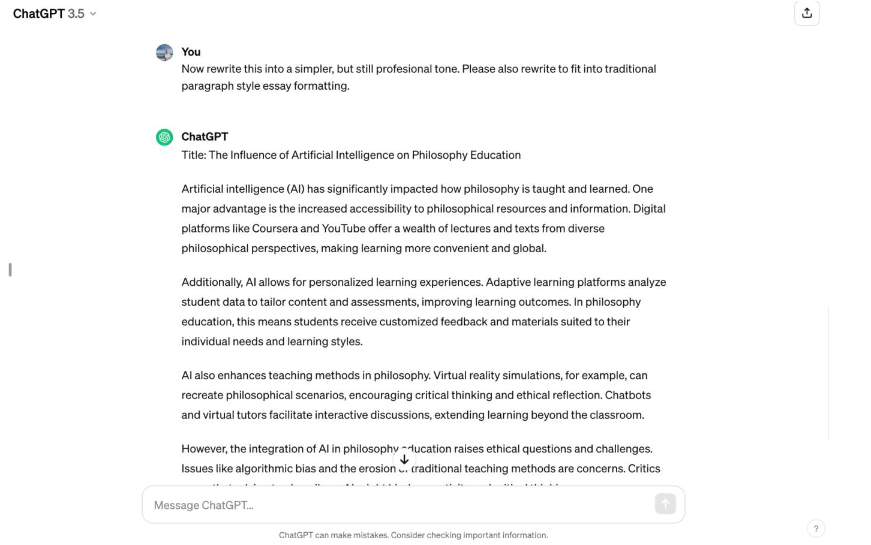

II. Premise 2

The second premise I have posited is that “generative AI has created new complications in the way we value and assess assignments.” To this end, I cite examples such as the paragraph I included at the onset of this paper. Generative AI is remarkably capable of generating content which is potentially difficult to distinguish from the content which might be produced by a student in the classroom. The example I provided used ChatGPT,6 one such generative AI model, which is rather elementary and becoming evermore obsolete even at the time of publishing as newer models are released, such as GPT-47 and Google’s Gemini.8 This suggests to me that if at least some subset of educators find themselves regularly unable to identify AI-generated content produced by what are fast becoming the older models of generative AI, what we see produced by the cutting-edge will persistently continue to elude detection, and will necessarily become a severe complication for teachers in their assessment of, and assigning value towards, student’s written assignments.

In considering this, we should now turn our attention to the manner by which philosophy education, and American academia at large, grew in response to John Dewey’s view of academia. Dewey’s pedagogy has become foundational in the way we traditionally conceive of teaching philosophy – and is responsible, in no small part, for many of the very values I discussed earlier – which are apparent across philosophy departments nationwide.9 How his pedagogy is currently applied often includes assignments which are especially susceptible to being supplanted by AI-generated content.10 Essays, comprehension assessments such as discussion forums and reading responses, and the-like, have become staples in the philosophy classroom. All forms of written assignments in particular, short or long, have become mainstays because they produce documents which are simpler to assess given a wide breadth of students and their individual styles and competencies, which has become that much more important in the continued commodification of the higher education environment. This focus, combined with an exceptional susceptibility to being fabricated and imitated by generative tools, denotes the aforementioned complication by which instructors struggle in assessing and evaluating these assignments.

I do recognise that academic misconduct is nothing new. Students have developed novel and ingenious strategies in order to, often by any means possible, not have to partake in direct engagement with class material (which I have already posited as being a foundational good). However, I argue that the threat posed by generative AI is different. Every student, whether inclined to academic misconduct or not, now has access to a platform which could reasonably be employed do the majority of coursework in many philosophy class settings, and this concern proves greater still when we consider how various forms of AI are being implemented as a default option in a variety of software platforms – from offering to auto-generate content in word processing platforms, to generating responses to messages as a part of email services, and even offering suggestions for what a user may be inclined to post or reply on various social media platforms.11 12

Given all this, it seems clear that generative AI has and will continue to undermine any justifiable belief that written assignment submissions are original and human-generated – therein complicating the way we go about assessing and evaluating a given assignment. To clarify, I am not arguing that we must necessarily forgo any and all essays, reading responses, or the like, just because it might potentially be susceptible to a student generating their submission by employing a generative AI platform. Instead, my argument is that we must critically consider why it is we value these particular assignments, that is, what goals or ends in our personal pedagogies are fulfilled by assigning them; furthermore, we must consider the best possible alternative to fulfilling those ends. Even if our answer to this question happens to result in the maintenance of our current approach, we ought still consider the sheer complexity of this new circumstance and adapt our methods to create environments in which we maximise the extent to which students engage fruitfully with course materials. (Note also, my conclusion simply claims that one ought to engage in the analysis of their approach to philosophy teaching and whether it is still practical. It makes no claims whatsoever as to which approach is more pertinent nor prescribes any actual desideratum for the purposes of philosophy education.)

III. Premise 3

I remain mindful that my third premise, “There are examples of current approaches to the pedagogy of philosophy failing us in assessing or prescribing value to these aforementioned assignments;” is the most contentious claim to defend without explicitly calling out my own peers or subjecting students who are self-revealing about having used generative AI content for assignments, both interpersonally and/or online, to heightened levels of scrutiny which could potentially result in retaliation against those students. Students, some of whom, for reasons I elaborate upon below, might not even realise they are committing academic misconduct in their use of generative AI.

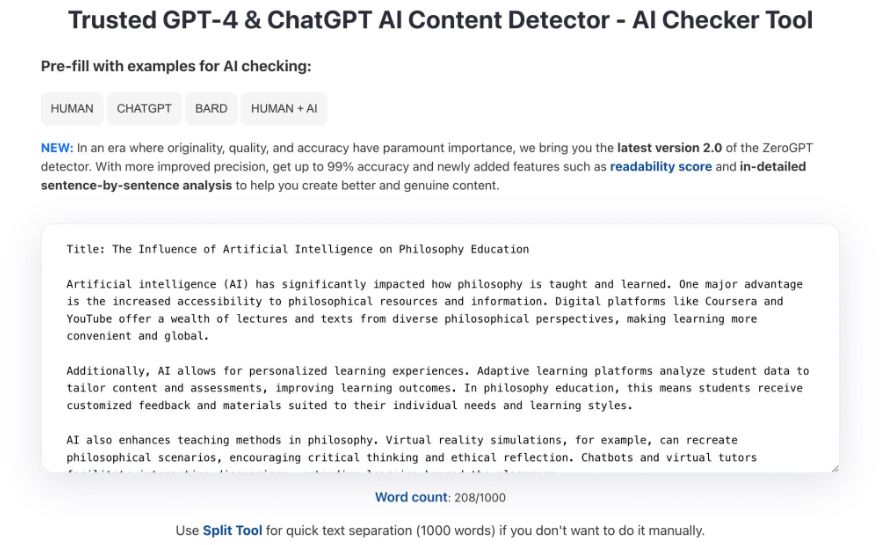

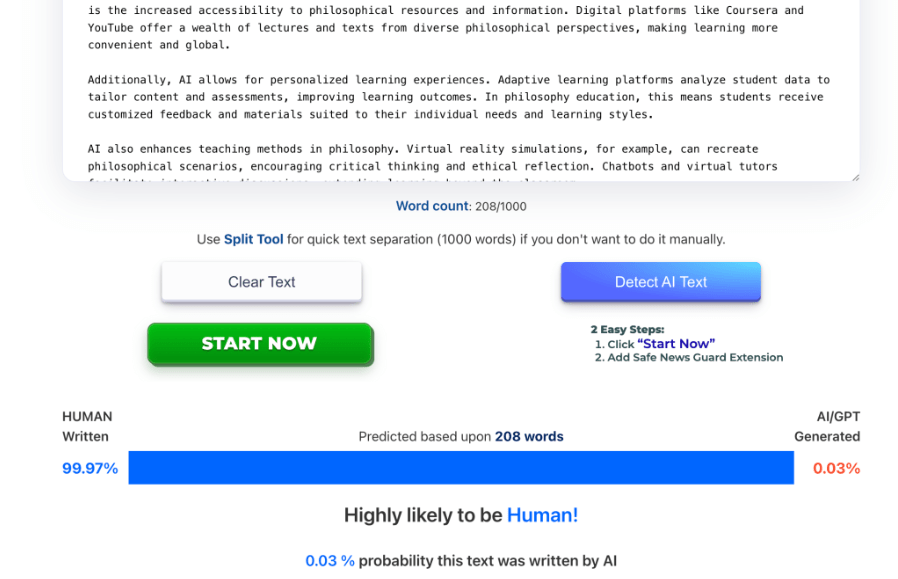

With the increasing prevalence of readily available generative AI, an arms race has begun, competing to provide so-called ‘GPT-detectors’, which claim to offer educators the ability to flag content as either human- or AI-generated. Yet, as ChatGPT’s parent company OpenAI explains in their ‘Do AI Detectors Work?’ section of an FAQ article written distinctly for concerned educators – these AI detectors are largely unreliable for determining what content has been generated by AI.13

Most AI-detectors do not provide error rates which might detail how often a false positive is provided for authentic, human-generated content.14 It has been demonstrated that texts which could not possibly be AI-generated, (being well over a few centuries old), can be flagged as AI-generated by these ‘detection’ platforms.15 Also demonstrated is that, by using ‘reworder’ platforms, or even by simply asking the same AI chatbot to rewrite what it originally produced, one could use AI to further create a given assignment in its entirety, while remaining undetected by GPT- ‘detectors.’16 Some research further suggests that these ‘detector’ platforms even discriminate against second-language English speakers and writers perhaps unintentionally, as they often use simpler grammar structure when putting their thoughts to paper.17

Even among students who mean well, the line between academic misconduct and the effective employment of the available resources can be incredibly unclear and difficult to distinguish for both teacher and student.18 For example, generative AI could be an infinite source of practice logic problems for philosophy of logic students to engage with in order to hone their reasoning skills – and it may seem that this is a perfectly acceptable, if not an astute, use of the potential beneficial application which AI offers to students. By contrast, while it seems clear that having generative AI create an entire essay is clearly academic misconduct, should it be acceptable for students to use AI chatbots to assist them in brainstorming ideas for an essay? Perhaps even just to generate a prompt? Should they be allowed to receive feedback on their essays from these chatbots? Questions like these so far remain unresolved, difficult to discern as being misconduct, and students engaging in these practices can’t really be properly said to be malicious in any capacity. Yet, until we designate clear frameworks for our students which clearly outline proper and inappropriate procedures regarding the use of AI, our expectations will remain ambiguous, with students, perhaps unknowingly, engaging in misconduct. To this end we will be left, in effect, incapable of adequately determining when this happens in the first place.

To date, the Ohio State University has yet to present an official statement which establishes detailed guidelines regarding where in particular the line, university-wide, for many of these difficult situations, is to be drawn. Instead, they have, for the most part, left the discretion up to individual departments, colleges, and teachers. That being said, this means individual philosophy instructors now have an even greater moral obligation to reevaluate their personal approach to philosophy instruction, given that, for the time being at least, there is no official University policy to which they may default or refer to on this specific issue.

Accounting for this, and at risk of exposing the operation underhand, as a student generally and of philosophy specifically, who is involved with other students in all kinds of programs, departments, and contexts, I can offer this unique insight to the teaching community which I believe provides me some justification in why I, as an undergraduate philosophy major, am able to write about the pedagogy of philosophy or impose some moral responsibility onto my instructors. As a student, I am privy to the relevantly situated knowledge that: not only is it my belief that students are capable of using generative AI to complete course assignments, I happen to know some number of my peers are using generative AI, (whether as a grammar and prose editing tool or to fabricate entire assignments-) and educators who would deny that any of their students use or have used platforms like ChatGPT are very likely mistaken and negligently disserving their students through their ignorance.

With that in mind, I want to quickly disengage from any allegations of fear-mongering which might arise naturally from this information. I am not misconstruing this situation as there being entire classes infested with or overwhelmed by students constantly committing academic misconduct. This is certainly not – at least not yet – the case. Many students, whether motivated by the perception of intrinsic value in doing philosophy or alternatively by a fear of their use of generative AI being discovered, are creating original, authentically composed human content and continue to engage with course materials. As far as I’m aware, this remains the majority of students, at least in my own personal experience, which I perceive to be analogous to my peers in similar situations nationwide. At higher levels of philosophy, it doesn’t even seem that content could feasibly be entirely AI-generated; although, I am rather sceptical that this will remain a restraint in the long-term. Nevertheless, I, as well as many of my peers, are able to clearly remember a handful of instances during which I personally watched a peer use or heard a peer claim to use generative AI in the process of completing an assignment. As such, I perceive this issue to be far more prevalent than most instructors are willing to acknowledge. Granted, of course, I am limited by which peers I speak with and which peers would be willing to abashedly admit something like this to me. Yet, given that my experience is familiar to those of other students I’ve spoken to, both in-person and by way of internet discourse on platforms such as Reddit or TikTok, I believe my knowledge provides an invaluable insight that many professors seem to be simply unaware of, or are able to justify their disbelief of it sans such situated knowledge. The potential threat of generative AI being employed to supplement a student’s engagement with class materials is a pressing concern rather than an abstract potentiality. We must realise that these conversations regarding the issue of generative AI are not preventative in nature, but rather, we are addressing real, practical concerns we are legitimately facing right now, in the present moment.

Note too that I previously defined the following moral imperative of “(…)in the context of teaching college-level philosophy, at the very least, it is valuable for students to engage directly with a given class’s materials.” Given this, anyone who concedes the veracity of my argument, need not prove that most students, or even those in a given class, necessarily, are actively using generative AI to complete assignments and thereby underserved by the traditional approach to philosophical pedagogy (t). Rather, I argue that the conceptual possibility of such a case, creates a present moral responsibility on instructors to – at the very least – reevaluate their approach to teaching philosophy, insofar as they can justifiably believe it is failing. If new approach (x) emerges, and more fully succeeds on average and in most contexts to allow for “students engag[ing] directly with a given class’ materials-”, then professors should use approach x rather than t, given that it is better able to meet the relevant condition. Otherwise, t remains an entirely valid, respectable approach to teaching philosophy.

IV. Conclusion

I began to consider these questions while participating in the Spring ‘24 semester course on ‘Teaching Philosophy,’ which provided me the opportunity to practically apply the methods of our philosophical pedagogy and deliver lessons to students. It remains an experience I greatly treasure as I seek to pursue a career in philosophy education. As part of my coursework, I was asked to personally consider why I believe philosophy education is important, and how I could measurably assess the extent of my success as an educator in achieving those ends.

However, for reasons that I mention above, generative AI has caused me to fundamentally question what philosophical instruction is going to look like for me should I successfully become an instructor. I found that when expressing these concerns to a few trusted role models, my concerns reflected a general anxiety which is widespread right now among academics in both the world of teaching philosophy, but also in education at large.

I do not believe that the greater community of philosophy educators yet appreciates how game-changing the increasing accessibility of general purpose generative AI chatbots might really be for the methods we employ for teaching philosophy and assessing student learning. I’ve heard it compared to the impact of the internet, the computer, and even the written word, in terms of the way it will radically reform the way we go about providing education.

In my anxieties, though, I have come back to the same foundational questions that I was asked as I embarked on the project of ‘teaching philosophy:’ Why do I want to teach philosophy? What do I find to be important about philosophy? What do I want my students to learn or be capable of? How can I know that they are capable of doing it?

The conclusion of my argument, as I have repeatedly noted, is not a solution or a suggestion as to the proper next steps for navigating philosophy education in this new age of generative AI; nor is it an answer to any of these questions I have reflected on. While I do believe I have more advice to offer towards these ends, that is beyond the scope of my thesis here. What I argue, simply, is this: generative AI is having a real impact, it’s here to stay, and it demands radically changing the ways in which we provide education in philosophy. It demands further that we open up the conversation – and we really should do this sooner rather than later. If we want the discipline of philosophy to remain relevant – or even the institutions of higher education generally – we must accept this reality and adapt to it. Otherwise, we will be performing a massive disservice to our students, or worse, we ensnare ourselves in a system which is becoming exceedingly irrelevant by no fault of its own.

AI technology has been talked up for decades, but it’s real, it’s here, and we are on a precipice overlooking the unknown, for all of us, as we navigate what exactly teaching for each of us will now look like in the age of generative AI. We should reorient our ‘compasses’ towards those foundational goals underlying why we do and teach philosophy. We should stride courageously into the adventure that awaits us as philosophy educators. In this manner we really are exploring uncharted territory. There will be trials and obstacles awaiting us as we carve this new path we are all simultaneously creating. This image, of exploring the uncharted, is salient for the gauntlet we are facing. It is an opportunity for change, as well as one for growth. Growth for us, as educators, but also for our students- who will rely on us to relay to them the skills of working alongside generative AI. The unknown can be terrifying. But I believe the conversations we must engage in now will influence the way philosophy is taught for decades to come. The conversation is well worth the risk. We must reconcile the needs of ourselves as educators with those of our students and the sheer computing power of generative AI. What the future of philosophy education looks like, in the face of this, is unknown and unknowable. Yet, I think, for the reasons mentioned above, we are morally obligated to embark on this journey if we intend to, as educators, maintain our conviction that students might engage with the ideas and resources of our classes. We are morally obligated to strike out on this expedition before us. We must explore the uncharted.

Notes

[1] For the prompt, I provided my introduction and argument of this paper and asked the chatbot: “Create an introduction to a philosophy paper which argues for the paper’s conclusion.”

[2] What are philosophy courses like in college? – Quora, n.d., https://www.quora.com/What-are-philosophy-courses-like-in-college.

[3]“Why Study Philosophy?,” Why Study Philosophy? | Department of Philosophy, n.d., https://philosophy.osu.edu/why-study-philosophy.

[4] “Introducing Chatgpt,” Introducing ChatGPT, n.d., https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

[5] What I mean by this is the philosophy behind, and practice of, teaching the subject of philosophy. This is not to say like a thought experiment about a potential pedagogy.

[6] I used the free GPT-3 version of ChatGPT to generate my introduction.

[7] GPT-4, n.d., https://openai.com/gpt-4.

[8] Sundar Pichai, “Introducing Gemini: Our Largest and Most Capable AI Model,” Google, December 6, 2023, https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-gemini-ai/.

[9] David L Hildebrand, “John Dewey,” essay, in The Routledge Companion to Pragmatism (Routledge, 2022), 26–34.

[10] I believe, notably, Dewey is worth mentioning because much of his thinking on individualising instruction and making learning collaborative could lend itself to how philosophy teaching is reimagined. Just because his ideas are applied ineffectively or maybe even inaccurately now does not mean his philosophy is not relevant for us in this discussion.

[11] “Write with Ai in Google Docs (Workspace Labs),” Google Docs Editors Help, n.d., https://support.google.com/docs/answer/13447609?hl=en.

[12] Microsoft Copilot for Microsoft 365, n.d., https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/enterprise/copilot-for-microsoft-365.

[13]“How Can Educators Respond to Students Presenting AI-Generated Content as Their Own? | Openai Help Center,” OpenAI FAQ, n.d., https://help.openai.com/en/articles/8313351-how-can-educators-respond-to-students-presenting-ai-generated-content-as-their-own.

[14] “AI Can Do Your Homework. Now What?,” YouTube, December 12, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEJ0_TVXh-I%C2%A0.

[15] See ‘appendix’ section [ex. 1].

[16] See ‘appendix’ section [ex. 2].

[17] Katarzyna Alexander, Christine Savvidou, and Chris Alexander, “Who Wrote This Essay? Detecting AI-Generated Writing in Second Language Education in Higher Education,” Teaching English With Technology 2023, no. 2 (2023), https://doi.org/10.56297/buka4060/xhld5365.

[18] I am reminded of a very current and controversial case about a student facing academic misconduct repercussions for using a grammar editing tool, Jeanette Settembre, “College Student Put on Academic Probation for Using Grammarly: ‘AI Violation,’” New York Post, February 21, 2024, https://nypost.com/2024/02/21/tech/student-put-on-probation-for-using-grammarly-ai-violation/.

Bibliography

“AI Can Do Your Homework. Now What?” YouTube, December 12, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEJ0_TVXh-I%C2%A0.

Alexander, Katarzyna, Christine Savvidou, and Chris Alexander. “Who Wrote This Essay? Detecting AI-Generated Writing in Second Language Education in Higher Education.” Teaching English With Technology 2023, no. 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.56297/buka4060/xhld5365.

GPT-4, n.d. https://openai.com/gpt-4.

Hildebrand, David L. “John Dewey.” Essay. In The Routledge Companion to Pragmatism, 26–34. Routledge, 2022.

“How Can Educators Respond to Students Presenting AI-Generated Content as Their Own? | Openai Help Center.” OpenAI FAQ, n.d. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/8313351-how-can-educators-respond-to-students-presenting-ai-generated-content-as-their-own.

“Introducing Chatgpt.” Introducing ChatGPT, n.d. https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

Microsoft Copilot for Microsoft 365, n.d. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/enterprise/copilot-for-microsoft-365.

Pichai, Sundar. “Introducing Gemini: Our Largest and Most Capable AI Model.” Google, December 6, 2023. https://blog.google/technology/ai/google-gemini-ai/.

Settembre, Jeanette. “College Student Put on Academic Probation for Using Grammarly: ‘Ai Violation.’” New York Post, February 21, 2024. https://nypost.com/2024/02/21/tech/student-put-on-probation-for-using-grammarly-ai-violation/.

What are philosophy courses like in college? – quora, n.d. https://www.quora.com/What-are-philosophy-courses-like-in-college.

“Why Study Philosophy?” Why Study Philosophy? | Department of Philosophy, n.d. https://philosophy.osu.edu/why-study-philosophy.

“Write with Ai in Google Docs (Workspace Labs).” Google Docs Editors Help, n.d. https://support.google.com/docs/answer/13447609?hl=en.

Appendix

Example 1

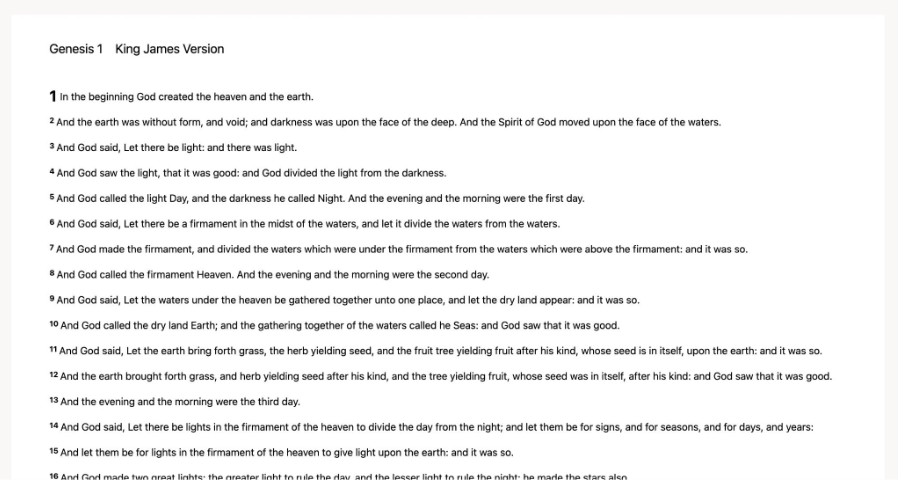

GPT detector flags Genesis 1 (King James Version) as 99.13% AI-generated:

Steps of Experiment:

PDF copy of Genesis 1 (KJV) obtained through BibleGateway.com

Copied and pasted into leading GPT, ZeroGPT

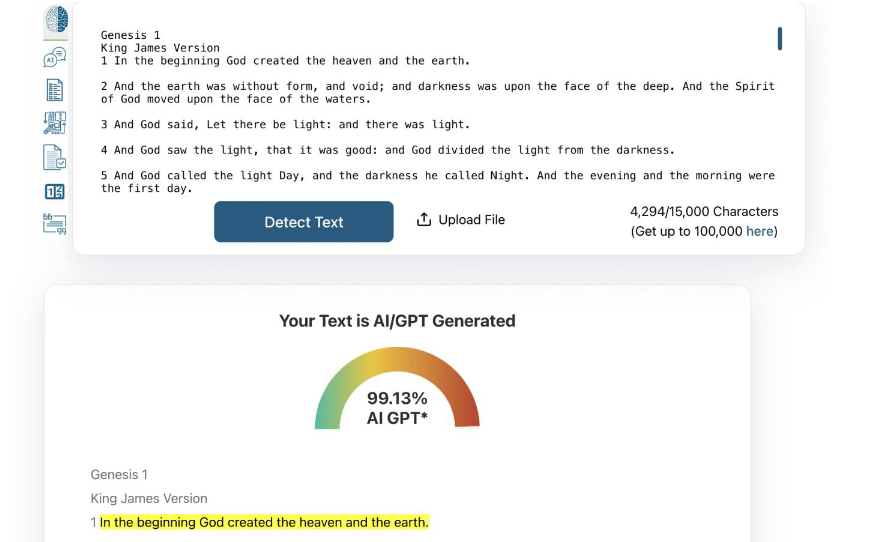

Example 2

By asking ChatGPT to reword the essay, the essay eludes GPT detection (99.7% human.)

Steps of Experiment:

Ask ChatGPT to create an essay

Ask ChatGPT to reword essay

Copy and paste into GPT detector

Scan for AI generation